Knowing how and when to program different types of muscle contraction is like having a cheat code for reaching your fitness goals. If everyone in the gym knew how to program to reach their goals, the diet and fitness industry would not be the multimillion-dollar juggernaut that it is.

Think back to the last time you were in the gym—certainly someone around you was swinging a dumbbell to perform a bicep curl with a weight that was too heavy. You might also have seen someone who quickly dropped to the bottom of their squat with minimal control.

Well, here’s a guide to how to use the science of concentric and eccentric contractions to get bigger muscles at the gym.

Concentric vs eccentric contraction for muscle growth

When you’re lifting weights, not all repetitions are equal. Savvy lifters and rehabilitation professionals use the types of contraction to help achieve their goals faster. The phases of muscle contracts are concentric, isometric, and eccentric.

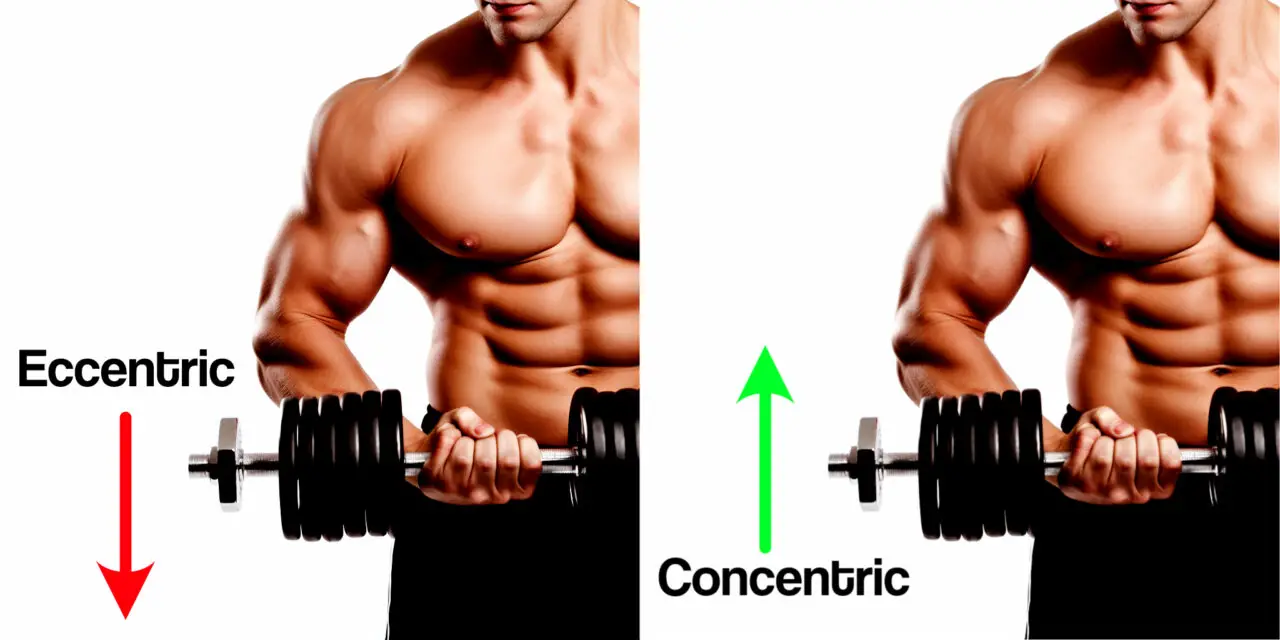

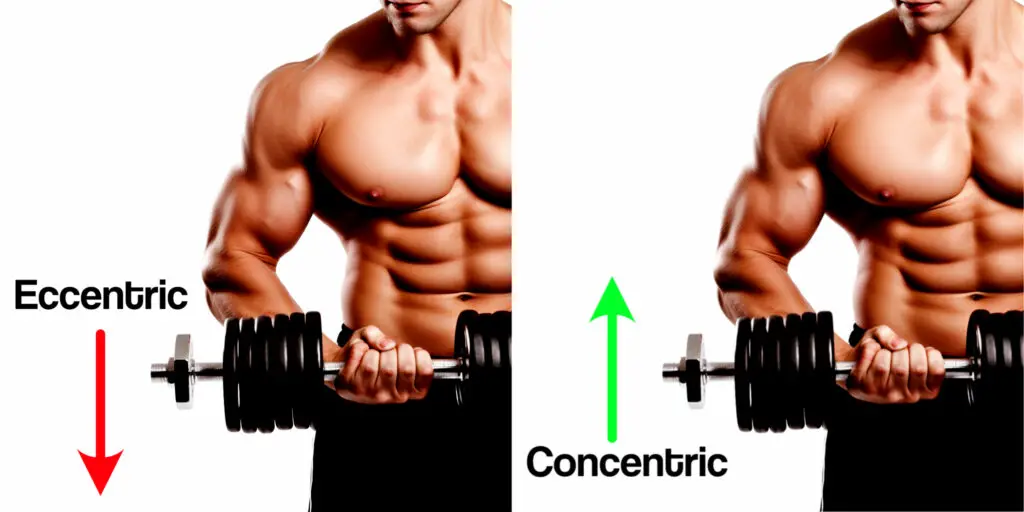

Concentric contraction is the shortening of the muscle. For example, in a bicep curl, which occurs as you lift the weight from your hip to your shoulder.

Eccentric contraction is the lengthening phase of the muscle. Back to the bicep curl example, this phase occurs as you lower the dumbbell from your shoulder back to your hip; you’re basically slowing down the effects of gravity as you control the weight rather than letting it fall back to the starting position.

(Original image by Element via Midjourney; illustration by Nick Ng)

In an isometric contraction, you’re generating force but there’s no movement at the joint. An example would be pushing into a wall or pulling on a locked door.

For years, research has suggested that the eccentric phase of muscle contractions is preferred when it comes to building strength and hypertrophy, although the exact reason why is not well understood.

It may be that more cross-bridges are formed between the actin and myosin filaments in the muscle fibers during eccentric contractions. The more cross-bridges that are formed, the more force the muscle can produce.

A 2009 meta-analysis examined 20 studies and found that eccentric training was better for muscle hypertrophy than concentric or isometric training alone. In 2015, another study echoed this finding on the primer of physiological and neural adaptations that occur with eccentric contractions. These authors assert that the increases in muscle damage and subsequent protein synthesis that occur with eccentric training lead to greater gains in muscle size.

Regardless of which type of strength training you use, eccentric contractions can become the emphasis. Using the SAID principle (specific adaptations to imposed demands), we know that your muscles will grow and change when loaded appropriately. Because eccentric contractions are stronger than concentric contractions, training “negatives” or using eccentrics can allow you to use heavier loads in future workouts.

When using machine-based training, this might mean you use both legs to lift the leg extension machine but only a single leg to lower the bar back to its starting position. You will know that your load is heavy enough for eccentric training if you cannot perform the concentric phase without help from another part of your body or your lifting partner.

The FITT principle (frequency, intensity, time, and type) is another guideline for workout design. These four variables can be changed depending on your workout goals. In the rehabilitation space, eccentric contractions are used in patients who have tendinopathies to get more “time under tension” because in vitro studies have shown that repetitive motion increases collagen production in the tendon.

For the non-injured lifter, eccentric training forces you to focus on the lowering phase of an exercise. Incorporating eccentrics in a FITT training plan could look like this:

- Frequency: Eccentric training that is properly programmed may result in moderate to severe DOMS so 1–2 times a week is sufficient

- Intensity: The weight should be heavier than you typically use; it should require help to complete the concentric portion of the exercise.

- Time: The most common lifting tempo is 2 seconds up and 2 seconds down but when focusing on eccentrics, the down phase could last as long as 10 seconds.

- Type: Choose exercises that are well suited to emphasizing the negative movement including squats, deadlifts, and pull-ups.

If functional training is more your style, eccentrics can work there, too. Using bands for assistance in pull-ups and dips to focus on the eccentric portion of the exercise while using the bands to help you return to the starting position. This means you can overload the muscle groups in the eccentric phase without the fear of getting stuck during the concentric part of the exercise.

An even easier way to focus on eccentrics during a functional exercise is push-ups; to highlight the lengthening portion of the exercise you can drop to your knees to perform the 10 second lowering phase and then return to full push-up position to press yourself up through the concentric contraction.

What about concentric contractions? Don’t they help build muscles?

A 2017 systematic review was not quite so convincing when it comes to the superiority of eccentric contractions during hypertrophy training. Brad Schoenfeld, who led that review, found that even though it did not reach statistical significance, the absolute increase in muscle hypertrophy produced with eccentric training was larger than that of concentric training (10.0% and 6.8% respectively).

“Essentially this means the eccentric component is at least as important, if not more so, for optimizing muscle development,” Schoenfeld said in an online interview. “It implies that people should focus on lowering the weights so that the muscles are controlling the descent (as opposed to simply letting the weights drop via gravity, as is often the case with lifters).”

Regarding his review, Schoenfeld emphasized that the biggest takeaway is that eccentric contraction “shouldn’t be considered an afterthought, as is often the case. It’s at least as important, if not more so than the concentric action.”

Further reading: [How to Train for Hypertrophy vs. Strength, According to Science]

How to apply concentric/eccentric movement in your workout.

Here’s what you can do to apply what you’ve learned about muscle contractions. Let’s say you’re using a pull-up resistance band to work on your pull-ups. The band assists with the concentric contraction while still allowing you to maximize your own eccentric contraction to lower your body to the start position. This type of heavy eccentric training can make you quite sore and may only be programmed a few repetitions at a time.

If you’re a novice,you may do 1 to 3 sets of 3 to 5 reps. The programming will depend heavily on how much assistance the band is providing.

Using an eccentric-focused tempo squat is another way you can incorporate this type of strength training into your workout. To increase the exercise intensity, take more time lowering yourself down before powering back up to an upright stance. A common tempo for eccentric squats is 4-1-1. This means you take 4 seconds to lower yourself to the bottom of your squat, pause for 1 second, and then push yourself back to the start position with a 1 second concentric contraction.

You can also do this with bicep curls, tricep extensions, leg press, bench press, and hamstring curls.

Does muscle soreness mean that my muscles are growing?

Muscle soreness that is a result of exercise-induced muscle damage (EIMD) does seem to be related to muscle growth. Though similar to delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), EIMD refers to the structural damage to muscle fibers that occurs when you are exercising under appropriate loads. This process includes damage to cell membranes, disruption to the contractile proteins (myosin and actin), and local inflammation.

EIMD seems to be a critical piece of the physiological process that leads to increased muscle size. According to Schoenfeld’s 2012 research, muscle soreness is often associated with the damage that happens when muscle fibers are subjected to loading that exceeds their capacity. While EIMD can have short-term effects on performance and pain, it appears to be necessary for achieving long-term hypertrophy goals.

Conversely, Nosaka’s research found that DOMS is not a good indicator of the muscle damage that leads to growth. Participants in this study had significant DOMS after eccentric exercise but did not have significant changes in strength or size. It appears that DOMS alone is not a good predictor of whether or not your program is adequate to create changes in muscle size.

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.