Active stretching is where you take a muscle group you want to stretch and contract its opposite muscle group without using external support to help you stretch. The objective isn’t necessarily to increase your flexibility; rather, it’s a way to prepare your body and mind for the upcoming activity within your own range of motion.

For example, if you want to stretch your hamstrings, you lie on the floor and raise one leg as high as you can until you feel a stretch. You contract your quadriceps (thighs) for a few seconds, relax the contraction, and lower your leg. Then you repeat this process a few times.

Some sources say that active stretching is more than just increasing flexibility; it’s a way to warm-up and prepare your muscles for whatever activity you are going to do. However, what does scientific evidence say about active stretching and athletic performance?

Active stretching vs. static stretching

Active stretching is a type of static stretching while static stretching is a broad term that includes all forms of stretching where you hold a stretch in a fixed position for a time period. Since active stretching is under the umbrella of static stretching, the guidelines for static stretching could be applied to the former.

Active stretching vs. passive stretching

Unlike passive stretching, active stretching does not need external forces to increase range of motion. Instead, when you “actively” contract a muscle group, you “relax” the opposite muscle group which allows more range of motion. This idea is based on reciprocal inhibition, where the agonists are under voluntary contraction, and the antagonists have reduced neural activity which allows the muscles to stretch further.

However, one Brazilian study in 2011 found that there is hardly any differences in knee extension flexibility between active and passive stretching among a group of 60 men.

What distinguishes active isolated stretching from other stretching exercises?

Active isolated stretching, or AIS, is a more specific type of active stretching that involves stretching a muscle for no more than two seconds and then return to its neutral position. This is repeated several times in intervals. Like standard active stretching, you would still contract the opposite muscle that you want to stretch but for a much shorter period of time. This is quite different than the standard guidelines suggested for static stretching.

Another difference is that you can do AIS with a partner or a tool that helps you stretch—like a resistance band or a half foam roller—similar to passive stretching.

There aren’t a lot of research that support whether AIS can improve specific types of sports and activities, nor are there any critical and systematic reviews yet. So, no one really knows if this type of stretching is better (or worse) than other forms of stretching for certain activities and populations.

Active stretching exercise examples

Supine hamstrings stretch with quadriceps contraction

Lie on the floor on your back with both legs extended toward the air with your knees slightly bent. Flex your toes toward your face. Lower one of your legs toward the ground while keeping the other leg in the same position by contracting your quadriceps.

Stop lowering when you feel a stretch in the opposite hamstrings. Hold this position for about 10 to 15 seconds, and then raise your leg back to its starting position. Repeat this exercise for 5 to 6 times one each leg. You may perform 2 to 3 sets.

Photo: Nick Ng

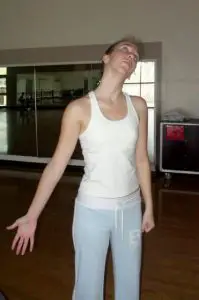

Thoracic mobility

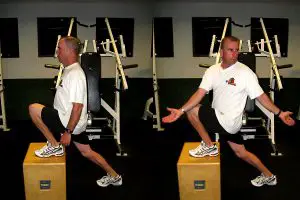

Lunge hip flexor stretching with glute contraction

Stand with one foot on top of a 2- to 3-foot high box or step, and lean your weight toward the front foot. Contract your glutes to increase the stretch in your hip flexors for 10 to 15 seconds. Then shift your weight back to the starting position and repeat the stretch on the opposite side. Repeat the stretch for 2 to 3 sets.

You may include stretching your lower back turning your torso toward the flexed hip as you hold the stretch.

Photo: Nick Ng

Triceps stretch with biceps contraction

Raise your right arm over your head and flex your right arm to touch your right hand to the back of your neck. You should feel a slight contraction in your right biceps. Contract your biceps to increase the stretch of your triceps. Hold the stretch for 10 to 15 seconds and repeat the stretch on the opposite arm. Repeat the stretch for 2 to 3 sets.

Biceps stretch with triceps contraction

Extend your right arm to your side with your right palm facing away from your body. Contract your triceps as you maintain the stretch for 10 to 15 seconds. Tilt your head to you left to increase the stretch if needed. Repeat the stretch on the opposite side, and repeat it for 2 to 3 sets.

Photo: Nick Ng

What does science say about active stretching and performance?

A 2012 review compared previous research on active stretching and passive stretching on muscle loss prevention. A majority of the research—in animal and human studies—found that passive stretching had little to no effect on preventing muscle atrophy, but active stretching could.

However, a few human studies that they summarized do find benefits of passive stretching, such as “significant changes in knee extension range of motion.” Passive stretching has been shown to decrease muscle stiffness for 10 to 20 minutes and improve greater range of motion in knee extension than dynamic stretching.

Although the literature offers mixed results, the weight of the current evidence leans toward active stretching as one intervention to minimize muscle atrophy. This could be beneficial for those who are bed-ridden or recovering from an injury.

More recent research, however, found contradicting evidence to the preview review, like one randomized-controlled trial in Japan in 2015. The researchers compared the effects of passive stretching and active stretching on hamstrings flexibility—with a control group. A total of 54 subjects were randomly selected for the passive, active, or control group with an equal distribution of nine men and nine women.

In the experimental groups, they laid on their back and bent their hips and knees at about 90 degrees as their starting position. They gradually extended their knee until they started to feel a stretch in the hamstrings.

In the passive stretching group, a researcher extended the knee further to a tolerable stretch.

In the active stretching group, the subjects extended their own knee by contracting their quadriceps.

In both groups, the stretch was held for 10 seconds and flexed the knee slowly for 10 seconds. They repeated the exercise for 3 sets. The control group did not stretch.

While both experimental groups had improved flexibility and the control group hardly had any increase, the researchers measured the results and found that the passive stretching gained more than double the amount of knee flexion (+15.8 degrees) than the active stretching group (+7.0 degrees).

The drawbacks of this research include having young, healthy subjects in their twenties, so we don’t know if this study can be applied to older populations. Future studies should also compare different stretch times. To extrapolate research into practice, it will take some consideration for whom you’re working with and your clients’ goals.

“If you look at all the research, it’s really an ‘it depends’ situation,” said Dr. Allan Bacon, who is co-owner of Maui Athletics in Hawaii. “If you have decreased flexibility, passive stretching is probably something that could help but probably isn’t the greatest thing to do before exercise. It’s probably better to do that post-exercise when you’re a little bit warmer and looser. ”

Conclusions about active stretching has its place in general fitness and rehab. Given the small number of studies and reviews about active stretching relative to other types of stretching, active stretching could be a part of warm-ups or a gradual way to regain strength and delay muscle atrophy if you are injured.

Bacon recommends that most of his clients do active stretching before a workout because that will “bring them to their end range of motion.”

“They do not need to achieve maximal flexibility if their sport or activity does not demand it,” he said.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.