Three massage therapists walk into a bar and saw that the bartender is grimacing in pain with one hand on his right lower back. Massage therapist A asks, “Hi Carlos, what’s bothering you?”

Carlos replies, “My lower back has been hurting for more than a week, and it seems to worse everyday. I take painkillers occasionally during work, but the pain comes back after I close the bar.”

Massage therapist A thought, “Maybe his quadratus lumborum and psosas are tight. Look at his hip. He has an anterior pelvic tilt and is leaning toward his right.”

Massage therapist B, who remembered that Carlos had went through a bad divorce last year, has been working as a bartender at this busy bar for over 12 years, and never complained about back pain in the past six years, thought, “His back may be tight, but after what he has gone through, maybe his back pain all in his head.”

Massage therapist C, however, asked Carlos, “Have you seen a doctor or physiotherapist? How have you been recently? Did you sleep well last night?”

There is a tendency of massage therapists to identify the cause of someone’s pain with a narrow, biased perspective. While there is no way of knowing exactly what caused the bartender’s back pain just by looking at him, considering his lifestyle, or reading his vitals, taking considerations of various factors — hence the accepted term “biopsychosocial” to describe diseases and pain — and how they interact with each other can help us decide the best treatment plan and how we communicate with a particular client or patient.

Brief background of the biopsychosocial model

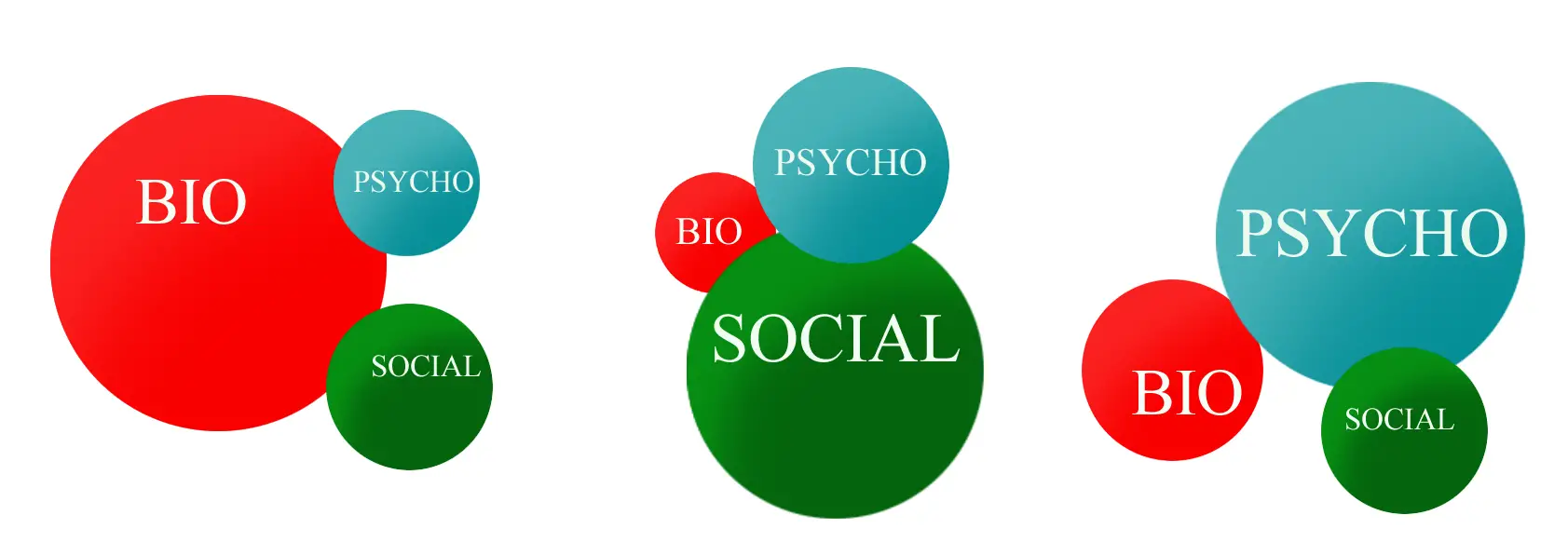

When the biopsychosocial model of pain and disease (BPS) was first introduced in medical literature in 1977 by psychiatrists Dr. George Engel and Dr. John Romano at the University of Rochester Medical Center, it was as revolutionary as the concept of a personal computer proposed by Jobs and Wozniak when they worked for IBM around the same time. (1) In the next four decades, the BPS model is often depicted as three equal-size circles, like the illustration on the left. However, this image may mislead some clinicians to think that these three ingredients carry equal weight in influencing pain.

Physiotherapy professor Dr. Gwendolen Jull from The University of Queensland in Australia wrote in an editorial that the BPS model has its limitations because of its broadness in definition and in nature.

“It does not guide, recommend or restrict which features should be evaluated in any domain. The clinician is free to choose from a variety of potential tests, so approaches to patient evaluation risk reflecting the professional or attitudinal bias of the clinician. Neither does the model inform on how one domain may or may not influence or interact with another domain.” (2)

Thus, each domain of the BPS model “will most likely change as the patient progresses through the course of the disorder.” And so, one or two domains would have a higher priority or influence than the others.

Difference circumstances can change the degree of each domain of the biopsychosocial model of pain. Image: Nick Ng

How could massage therapists reframe and apply the biopsychosocial model of pain?

Because the contributions to pain varies among each person, it makes sense that certain domains contribute pain more than another. For example, in the model on the left in the feature image, a patient with a gunshot wound or a sprained ankle during a run would most likely experience pain due to biological reasons. While psychosocial factors may not play a huge role in such acute injury, they still contribute to how much pain one experiences depending on a context. If one patient catastrophisize an ankle sprain more than another, the former would likely experience higher pain intensity.

In the middle model, social context may affect how much pain a patient, even after the tissues have healed. This patient may experience the same injury as the one in the first model, but she might worry that her injury might prevent her from competing a track and field event, limit her ability to care for her kids, or affect her income in which her job requires her to stand for a long time. This model may interchange with the third model since the social context of the injury affects her thoughts and emotions.

“It is time for the pendulum to steady. It is neither a biological model nor is it a psychosocial model, rather it is a biopsychosocial model,” Dr. Jull suggested. “The model is not without its critics, but the sentiments of the model are highly commendable and should be embedded in research and patient care.” (2)

So applying this to our friendly bartender’s case, perhaps it’s better to ask questions to find out more about Carlos’ pain rather than project what therapists think is going on with him. The biopsychosocial model of pain doesn’t necessarily change what massage therapists do; it changes the way they communicate and deal with their clients or patients, a way to understand their problem in a broader spectrum.

More on pain

Pain Science 101 for Massage Therapists

Why Massage Therapy Needs to be Trauma-Informed

Why Massage Therapists Need to Understand How Pain Works

References

1. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977 Apr 8;196(4286):129-36.

2. Jull G. Biopsychosocial model of disease: 40 years on. Why way is the pendulum swinging? British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;0:1-2. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097362

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.