A group of researchers and physiotherapists recently challenged the current diagnosis and management of sacroiliac joint pain. Led by Dr. Thorvaldur Palsson from the Department of Science and Technology at Aalborg University in Denmark, the team questioned a few common ideas among clinicians about why the sacroiliac joint is painful among many patients.

Traditional explanations for sacroiliac (SI) joint pain is that there’s some sort of movement dysfunction or structural abnormality in the joint, such as asymmetry, joint stiffness, weakness, and instability.

Physiotherapists would assess the SI joint by using pain provocation tests to see if it’s the source of pain.

Palsson et al. described a few of such tests by applying mechanical stress directly to the pelvic girdle or indirectly through the hip to cause shear stress in the SI joint. These tests are used to discriminate SI joint pain from other types of low back pain.

While these tests can help clinicians to be informed on whether the SI joint is involved or not, pain provocation tests don’t tell them why there is pain, Dr. Palsson said in an online interview with Massage & Fitness Magazine.

“These tests have been shown to be sensitive and specific for determining whether the source of symptoms lies within the SI joint complex or not. This was done by using CT-guided intra-articular blocking protocols,” he said.

Palsson mentioned that some studies show that anaesthetizing joints outside of the SI joint can provide short-term reduction in SI joint pain.

“Peripheral sensitization does not equate to symptoms, and a positive clinical test demonstrating sensitivity of the SI joint complex does not suggest changes in movement of the SI joint,” Palsson said.

What is sacroiliac joint pain?

Sacroiliac joint pain can sometimes be mistaken for typical low back pain or hip pain in the buttocks because the symptoms are similar. Moscote-Salazar et al. distinguishes two types of sacroiliac joint pain.

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

A joint dysfunction doesn’t necessarily cause pain, but it may likely increase the risk of pain. This refers to joint movement that deviates from its normal position that conform.

Sacroiliac joint syndrome

This is commonly referred to SI joint pain. Moscote-Salazar et al. refer it to “a wide range of pathologies capable of generating pain in several locations with common innervation with the sacroiliac joint.”

This explains why SI joint pain symptoms are similar to other types of low back pain and hip pain. The researchers suggested that clinicians should look at the bigger picture to see how SI joint pain is integrated with other body parts rather than treating it as an isolated problem.

What does sacroiliac joint pain feels like?

Many patients describe SI joint pain as stabbing, dull, or achy at the joint. Sometimes the pain radiates down the leg along the posterior thigh, rarely going below the knee.

In some cases, the pain can feel like a typical low back pain with the similar dull, achy, or sharp feeling. Pain tends to amplify when patients are sitting, climbing stairs, or lying on the side which has the pain.

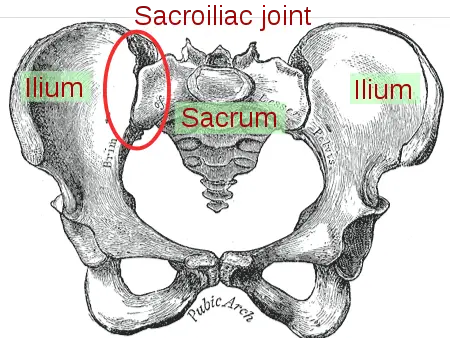

Where is the sacroiliac joint?

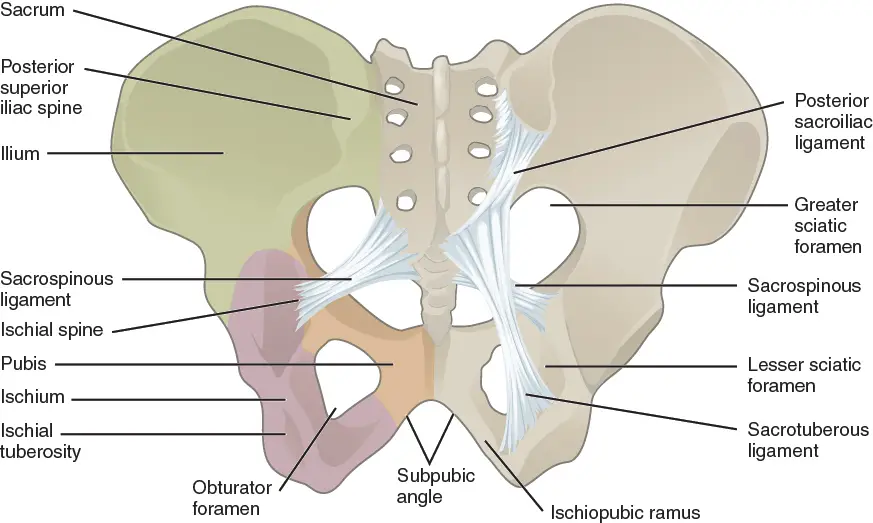

Image: Gray’s Anatomy

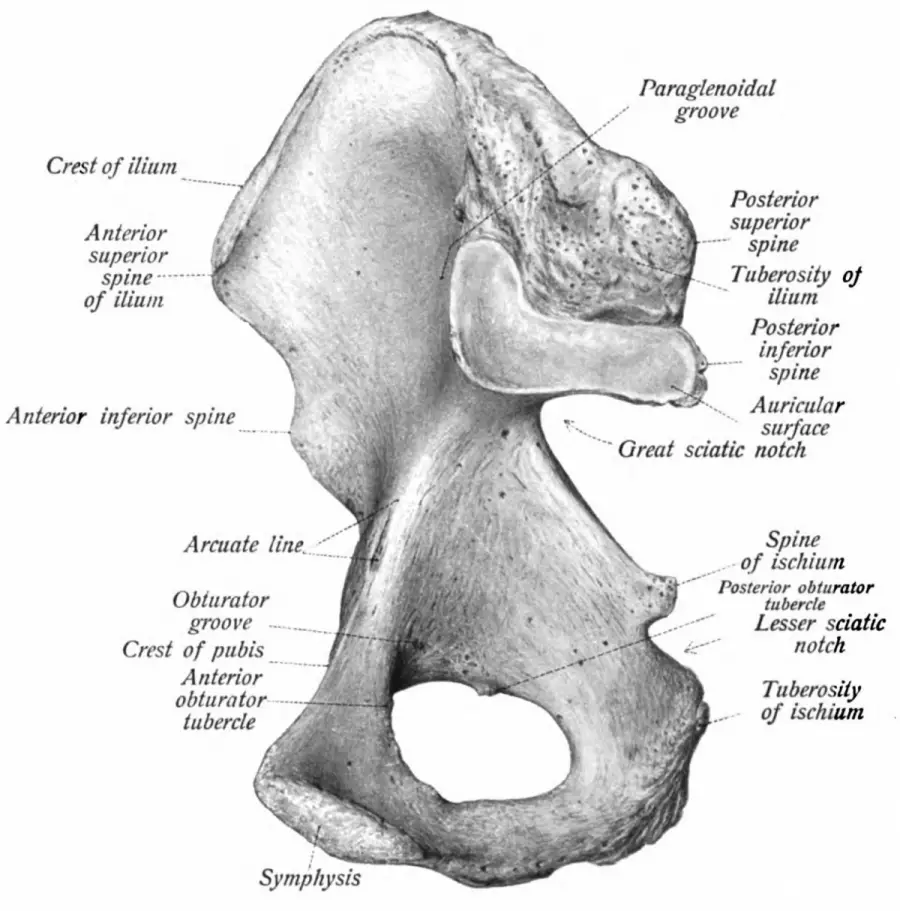

The SI joint is located at the pelvis. It connects the ilium and the sacrum with a diarthrodial synovial joint. This means that its articulations have two types of cartilages: hyaline cartilage on the sacral surface and fibrocartilage on the iliac surface.

The sacral surface has a series of depressions while the iliac surface has elevated ridges where the two surfaces form an interlocking joint.

This “lock” limits the degree of the SI joint’s movement to no more than 8 millimeters in “sliding” between bones. It can move up to 2 to 8 millimeters in rotation in all planes of motion. That’s less than half the width of a dime.

The SI joint’s primary role is to reduce force generated from the lower body—like a shock absorber for the spine—with the help of the thoraclumbar fascia and sacroiliac ligaments.

Nerve innervation comes from the ventral rami of L4 and L5, the superior gluteal nerve, and the dorsal rami of the L5 to S2. However, some people have innervation only from the sacral dorsal rami, which can cause different pain patterns from the SI joint.

Source: Essential Clinical Anatomy. K.L. Moore & A.M. Agur. Lippincott, 2 ed. 2002. Page 263. Image: Mikael Häggström.

What causes sacroiliac joint pain?

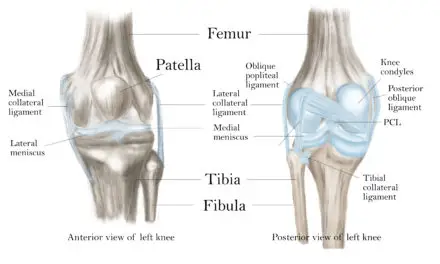

Like most joint pain, sacroiliac joint pain usually stems from nociceptors within the anterior capsular ligament and the interosseous ligament of the SI joint.

Researchers from the VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam identified different neuropeptides within these structures that contribute to pain, which are specialized proteins that help neurons “talk” to each other.

When a person senses a threatening stimulus, such as from a visual or tactile sensation, these neuropeptides are released from the dorsal horn of the spinal cord.

Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site. http://cnx.org/content/col11496/1.6/, Jun 19, 2013. Image: OpenStax College

Environmental, biomechanical, and physiological factors could increase the risk of getting SI joint pain, not just biomechanical factors.

Researchers from John Hopkins School of Medicine identified various types of arthritis and rheumatism are the two most commons causes, followed by ligament and muscle injuries, such as from a fall or car accident.

Abnormal gait patterns, persistent strain on the sacroiliac ligaments, leg length discrepancy, scoliosis, pregnancy, and spine surgery can also increase the risks. Keep in mind that these are risk factors, not a cause to having SI joint pain.

Can you “feel” sacroiliac joint rotation?

Having an “unstable” SI joint as the primary cause of pain is usually the blame, but this idea is not consistent with the current understanding of the SI joint’s anatomy, biomechanics, and neuroscience.

With the sacrum wedged between the ilium which are supported by the sacral ligaments and pelvic muscles, it would take a tremendous amount of physical trauma to make the joint “unstable.”

Since a majority of patients have such pain without such trauma, the unstable narrative is unlikely. Palsson mentioned that detection of SI joint movements with palpation is also highly unlikely because the SI joints have a tiny degree of freedom of movement.

In his paper, he and his team wrote that the SI joint rotates an average of 0.2 degrees—or about 0.3 millimeters—in a standing hip flexion test.

“Given these challenges in detection of movement, it is not surprising that tests for movement dysfunction are not reliable,” they wrote. “Directly attributing SIJ-related pain to movement dysfunctions causing increased peripheral nociceptive input from sacroiliac joint tissues, is a flaw in reasoning, mistaking association for causality. Positive pain provocation tests are likely indicative of increased sensitivity of the tissues, which might to some degree be subsequent to tissue loading.”

“Clinicians’ ability to reliably detect the anatomical landmarks and their excursion when the joint movement (actively or passively) is poor,” Palsson explained. “Pain itself—in the absence of pathology—can cause changes in the way we move which can affect what is felt during palpation.

“This has been demonstrated in several experimental pain studies. With these in mind, it appears that the notion of movement dysfunctions of the SI joint and clinicians being able to detect too much or too little motion lacks plausibility. Given that, you have to wonder whether conveying [such] messages, which are based on guessing at best, is helpful for patients or clinicians.”

Palsson mentioned that sensitivity in the peripheral nerves in the skin can be a contributing factor, but it’s only a single factor. He suggeseted that clinicians should also consider spine loading, how the patient thinks about pain, and lifestyle factors.

What manual therapists can start doing is to avoid fear-provoking messages about patients’ condition, help patients reframe their beliefs about, and explore what they can do. One way is to use the “7 C’s” in narrative medicine as a guideline to help therapists communicate.

For example, if a patient was told that their pelvis is “weak and unstable” because of “poor posture,” the therapist could ask, “Well, could there be an alternative reason for the pain?”

Or the therapist could help the patient explore other ways to move without less or no pain: “Ok, let’s find out what you can do today. Shall we try this exercise?”

“With the sacrum wedged between the ilium which are supported by the sacral ligaments and pelvic muscles, it would take a tremendous amount of physical trauma to make the joint unstable.”

“Messages that focus on weakness or fragility are more likely to maintain or worsen the condition instead of helping the patient,” Dr. Palsson warned. “Dr. Samantha Bunzli and her colleagues had shown us that by helping patients making sense of their pain and changing their pain beliefs may help them overcome e.g. movement-related fear, which is often one of the hurdles patients need to overcome during recovery.

“This can be achieved by giving them insight into their own condition and helping them to gain independence from health care professionals.”

Sacroiliac joint pain relief

A 2021 review of SI joint pain suggested that conservative treatment should be used first before considering invasive treatments. These options include:

Physical therapy

Physical therapy for SI joint pain involves a variety of methods, including exercise, joint manipulation, and athletic taping. A 2017 systematic review of nine qualified studies found that manipulation may be more effective in reducing pain and disability than exercise, taping (Kinesio tape) and rest.

However, the small number of studies and subjects may skew the results, so take the findings with a grain of salt until more data is available.

Pain medications

A 2017 systematic review examined 79 studies on the effectiveness of NSAIDS (70) and benzodiazepines (9) for general low back pain. They found that these medications have “small to moderate” short-term effects.

If these fail, the reviewers suggested nerve block injection or radiofrequency neurotomy.

Nerve block injection

Physicians may inject pain-killing medication into or near the SI joint. A 2020 review of the treatment and diagnosis of SI joint pain found that those who get a corticosteroid injection get pain relief for about six to ten months in 80% of the cases.

But the authors warned that these studies are low-powered, meaning that the magnitude of the effect may not be that clinically significant. In other words, the researchers could not tell if the treatment is that better than no treatment at all.

Radiofrequency neurotomy

This is a minimal invasive treatment where needles are put near the nerves of the sacroiliac joint. Heat from the electrical current in the needles are channeled into the affected nerves, which is supposed to lessen or deaden the pain in the long run.

But does it work? Based on a 2019 meta-analysis by a group of Taiwanese researchers, they found that the radiofrequency neurotomy can provide better low back pain and SI joint pain relief than sham treatments and various types of conservative treatments.

However, the number of studies and subjects they included was small, so there may be some bias that skewed the data, such as the different ways of how the experiments were set up.

This is not a substitute for medical advice nor is it an endorsement of any treatments. Always check with your physician or qualified healthcare professional on what treatment options are best for you.

How clinicians apply the modern narrative of sacroiliac joint pain

While there has been more than 10 years of data and research that did not support the biomechanical narrative, many manual therapy schools are still behind in catching up to the current research. Updating the curriculum seems like an obvious solution, but this would involve “a consensus at many levels” from management to teachers, Dr. Palsson said.

And if manual therapists are not palpating the pelvis, what can they do based on current evidence?

Dr. Palsson suggested the following:

-

Explain how pain works tailored to the individual presentation based on the biopsychosocial model;

-

Constructively address unhelpful/aberrant health beliefs;

-

Promote reassurance regarding structural integrity of the pelvis or SI joint;

-

Design and discuss a management plan that is aligned with points 1 to 3.

“Even though these suggestions are reduced to four points, we are aware that this is not an easy task. Explaining how pain works, for example, is contingent upon us understanding how it works,” Palsson said.

“This is an evolving field where more and more knowledge is continually emerging. A lot of what we know about pain can and should be implemented in curricula and be used in combination with other course modules, especially those focusing on assessment of the musculoskeletal system.

Palsson emphasized that the point of their research paper isn’t to toss out techniques or tools that therapists are already using.

“We wanted to encourage clinicians to place themselves as the sources of truth for their patients instead of contributing to misinformation.

“The outcome of any given intervention will always to some extent relate to clinician and patient preferences. What we want clinicians to take away is that they consider and choose their words and interventions wisely and avoid mixed messaging based on a thin foundation, like providing mobilizing treatment and prescribing stabilizing exercise. These messages should be limited to what we do know from the available evidence and explained in laymen terms.”

Editor’s note: This story was first published on Nov. 11, 2019. Updated July 25, 2021.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.