Gluteal tendinopathy typically affects sedentary people, but it can also be problematic among those participating in running and other athletic activities. It’s the most common lower limb tendinopathy, and it’s nearly three times more common in women than men.

Gluteal tendinopathy may affect as many as 25 percent of women more than 50-years-old and has recently been understood as part of a cascade of signs and symptoms associated with greater trochanteric pain syndrome, which causes pain down the lateral side of the leg and buttocks to the outer knee.

One of the most contentious topics in hip rehab is the existence of “gluteal amnesia.” First described by Dr. Stuart McGill, gluteal amnesia is the inability to engage the hips during athletic activities or exercise, which is believed to have a negative effect on performance and potentially increase the risk of injury.

This condition has also been referred to as “dead butt syndrome,” or defined as the gluteal muscles being “turned off” or “inhibited.”

This popular theory has been refuted by electromyographic (EMG) studies of the hip muscles that have found no consistent firing pattern in asymptomatic subjects.

So if people with no hip pain already demonstrated a lack of firing consistency, how would this justify that people with “gluteal amnesia” and similar labels have inconsistent firing patterns in their glutes?

In that EMG study, the researchers found that muscle activation order is very different among each subject. The only consistent finding is that the gluteus maximus is the last to be activated.

All things considered, it’s likely incorrect to label hip pain and symptoms as “gluteal amnesia” or “dead butt syndrome.” Clinicians must take the time to recognize individual differences in movement patterns and identify root causes of dysfunction to craft the most appropriate treatment plan.

Anatomy of the gluteal muscles

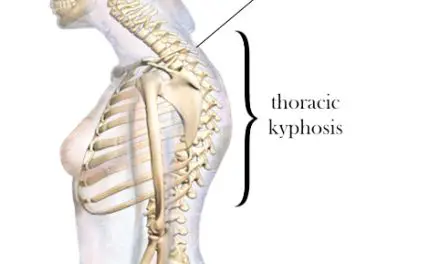

The gluteus medius is a broad, thick muscle that stretches from the iliac crest of the pelvis to the greater trochanter. The gluteal tendon is strong and flat with two insertions on the trochanter at the superoposterior and lateral facets.

There’s a bursa that sits between the tendon and the bony trochanter where it serves to decrease friction between the soft tissue and bone.

Similar to the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus is a fan-shaped muscle that originates on the outer surface of the pelvis’s ilium and inserts at the anterior facet of the greater trochanter. The superior gluteal nerve innervates both muscles.

Detail image of the gluteal muscles

The gluteus medius primarily abducts the hip joint, such as moving your leg away from your body laterally. It’s responsible for maintaining a level pelvis during the single-leg phase of the gait cycle.

It also acts as an internal or external rotator of the femur, depending on which portion of the muscle is active. The gluteus minimus assists the gluteus medius in these roles.

Gluteal tendinopathy symptoms

Patients with gluteal tendinopathy typically have moderate to severe pain in the lateral hip area. Historically, pain in the greater trochanter region has been diagnosed as trochanteric bursitis but has recently been described, along with gluteal tendinopathy, as part of greater trochanteric pain syndrome.

Similar to hip arthritis, gluteal tendinopathy generally starts as a subtle, nagging pain that gradually worsens over time. Some of the symptoms the patient may report include:

- Tenderness to touch over the lateral hip, specifically in the greater trochanter area;

- Pain with side-lying on the involved side;

- Pain with standing, walking, etc.;

- Pain when sitting for long periods of time or with their legs crossed in any fashion;

- Decreased strength on the symptomatic side.

Weakness of the lateral hip stabilizers is typically first identified by a Trendelenburg sign, which is where one side of your hips “drops” when you load your foot on the same side as you walk.

While some of the symptoms of gluteal tendinopathy overlap with hip osteoarthritis, one way to tell the difference is your ability to put on your socks and shoes.

Hip osteoarthritis limits the motion at the joint which impedes your ability to cross one leg over the other; gluteal tendinopathy may create pain in this position, but it does not typically limit your ability.

What are the causes or risk factors of gluteal tendinopathy?

Gluteal tendinopathy may be caused by “wear and tear,” where the compression between the greater trochanter and gluteal tendon decreases blood flow in the tissue and interrupts the normal recovery and regeneration after an activity. The anatomical relationships among the femur, pelvis, lumbar plexus, and soft tissues may also cause this increased compression directly or indirectly.

Joints

Degenerative joint disease and other hip pathologies can become risk factors for developing gluteal tendinopathy, secondary to altered movement patterns and gait deviations.

Osteoarthritis, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), and avascular necrosis are all associated with pain and range of motion restrictions that may cause you to lessen the load on your painful leg when you walk, which results in increased adduction (hip and leg moving toward the midline of your body) on the contralateral side. This compensation may lead to gluteal tendinopathy.

Bone

The shape of the female pelvis has been posited as a potential risk factor for developing gluteal tendinopathy because of a larger Q-angle. The wider pelvis may require more hip abductor strength to control hip adduction during squatting, jumping, running, and other movements.

Another risk factor is femoral offset, which is the distance from the center of rotation of the femur’s head to a line bisecting the long axis of the femur. Abductor strength varies depending on this angle as the offset influences the force that the gluteus medius needs to maintain the balance of the pelvis.

Coxa vara, a decrease in the angle between the femur’s neck and shaft, may also influence the development of gluteal tendinopathy as this deformity tends to cause the hips to adduct.

Nerve and muscles

Some people may blame an irritated or pinched nerve near the gluteal tendon to cause their lateral hip pain, but research finds that tendon pathology and muscle atrophy of the lateral glute muscles are more likely to increase the risk of gluteal tendinopathy than having nerve issues.

The researchers also found that younger subjects had higher degeneration of the superoposterior insertion of gluteus minimus while older adults had such degeneration at both attachment sites. This suggests that the superoposterior portion is prone to earlier degeneration.

Most of the symptoms at either the superoposterior or lateral facet were not associated with atrophy, which may indicate that attachment of one tendon is enough for maintaining muscle bulk.

An additional indirect cause of gluteal tendinopathy may be a low back injury that causes nerve irritation at the levels responsible for the gluteal muscles. The hip abductors are innervated by L4, L5, and S1 as well as the superior gluteal nerve. Injury to any of these structures can result in weakness.

Ninety-five percent of lumbar disc herniations occur at these levels. Also, the pain and dysfunction associated with piriformis syndrome may create a Trendelenberg gait or a similar gait that increases compression of these tissues on the affected side.

Diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy

As with most musculoskeletal conditions, gluteal tendinopathy is best diagnosed using a combination of subjective report, symptom presentation, and a cluster of clinical tests. Common tests used in the differential diagnosis of gluteal tendinopathy include: FABER, single-leg stance test, resisted external derotation test, passive hip adduction, and palpation.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

FABER test

A positive FABER test can be used to discern between gluteal tendinopathy and hip osteoarthritis. A patient with a reduced hip range of motion due to osteoarthritis will have pain and difficulty getting into the position needed to conduct this test.

Also, the test position is similar to that used when you don shoes and socks, which may help the clinician to correlate the clinical findings with the patient’s health history. Research has shown the FABER test to be excellent at ruling gluteal tendinopathy in and out.

Single-leg test

The single-leg stance test, sometimes referred to as the Trendelenburg Test, which involves asking the patient to stand on their affected leg for 30 seconds. A positive test is indicated by a pelvic drop on the opposite side of the affected leg, indicating weakness of the hip abductor musculature or pain. This test is highly sensitive and specific.

Photos: Penny Goldberg

Resisted external derotation test

The resisted external derotation test is performed with the patient lying on their back with the hip and knee flexed to 90 degrees and the hip externally rotated.

The patient is then asked to return the affected leg to neutral rotation; the test is positive if pain is reproduced. This test has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for detecting gluteal tendinopathy with values of 88 and 97.3 percent, respectively.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Passive hip adduction

Passive hip adduction is performed with the you lie on your side with the affected side toward the ceiling. Your bottom leg is bent comfortably while your top leg is supported by the clinician.

They would passively move your leg through a full range adduction with some compression to your hip. In full adduction, the insertions of the gluteal tendons are under both tensile and compressive load which will elicit pain if you have gluteal tendinopathy.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Imaging may be necessary to rule out the need for surgery. Radiography is typically used, but it’s limited ability to detect soft tissue lesions makes it somewhat undesirable for this condition.

For soft tissue evaluation, ultrasound may be preferable due to lower cost and ease of availability. Ultrasound may be less sensitive than MRI, and its use may be limited by the operator’s experience.

Though more costly and less available, MRI is the gold standard in diagnosing gluteal tendinopathy as it allows clinicians to visualize direct (e.g. swelling, changes to tendon morphology) and indirect (e.g. fatty atrophy) signs of tendinopathy.

Remember that different types of hip pain can have similar symptoms, and they can be mistaken for another like sciatica or IT band syndrome. As with any injury or illness, you should consult with a physician or qualified medical professional to determine the best personal treatment plan.

Exercise for gluteal tendinopathy

Research finds that isometric exercises early on in gluteal tendinopathy could reduce pain.

Although it hasn’t been studied in gluteal tendinopathies, research on knee tendinopathy recommends holding a relatively heavy quadriceps contraction (think leg extension machine) four times for 45 to 60 seconds, several times each day, to increase pain threshold.

You could also do this by holding your leg out straight and squeezing your thigh muscle as hard as you can.

Another recent study showed similar results with the same type of exercise at near-maximum effort. This dosage provided near-complete pain relief immediately and up to 45 minutes post-exercise.

A progressive strength program helps reduce pain and improve load-bearing capacity of the tendon in the early stages of tendinopathy.

Recent research has debunked the classical idea that eccentric training is the preferred method for rehabilitating tendinopathies.

An eccentric contraction is the lengthening portion of a muscle during an exercise. For example, when you squat down the muscles on the front of your leg lengthen as you lower yourself down (eccentric) and shorten as you rise back up (concentric contraction).

Rehab programs that focus solely on eccentric training are not only insufficient but may further aggravate pain and symptoms.

Photo: Tim Arndt

This “old school” thinking should be replaced by heavy, slow resistance training performed in mid-range abduction. Keeping the patient out of adduction prevents compression of the gluteal tendons at the greater trochanter and avoids placing surrounding musculature at a mechanical disadvantage.

When possible, exercise programs should incorporate isolated hip abductor strengthening in weight-bearing positions.

Hip abduction for runners

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Hip abduction loading

Loading of the hip abductors in exercises, such as standing abduction on a Pilates reformer, slide board, or slippery (tile) floor allows for weight-bearing stimulus coupled with the ability to adjust resistance while minimizing tendon compression. This allows the exerciser to work in mid-range abduction.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Trailing leg abduction

If a Pilates reformer or slippery floor is not available or is unsafe for a patient, simple side-stepping with emphasis on trail leg abduction can be used.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Contrary to popular thinking, targeted abductor strengthening is weakly correlated with functional tasks, such as a single leg squat, nor did improved abductor strength affect knee valgus in patients with knee pain.

Thus, exercises that control hip adduction in squatting, single-leg stance, stair climbing, running, or other sport-specific movements should be emphasized.

How to sleep with gluteal tendinopathy

The first step in the management of insertional tendinopathies is minimizing positions or activities that involve repetitive or sustained compression, particularly when compression is coupled with high tensile loads.

Patients with gluteal tendinopathy should avoid:

- Sitting cross-legged

- Sitting with knees together

- Standing with weight shifted to one side

- Lying on affected side

- Stretching in hip adduction as is typical for glutes or iliotibial band

Finding comfortable sleep positions may be a challenge for those with gluteal tendinopathy. If patients prefer to sleep on their unaffected side, they can place a pillow between their knees to limit the adduction allowed at their affected hip.

Photo: Penny Goldberg

Sleeping in supine with the hips in slight abduction is most preferable while side-lying with the top hip flexed and adducted should be avoided whenever possible.

Massage and gluteal tendinopathy

Gluteal tendinopathy isn’t typically associated with active inflammatory processes, but there could be periods of inflammation during its development. Deep friction applied to the tendon may be effective at decreasing pain and improving strength and mobility, but it’s not for everyone.

Tania Velásquez, who practices and teaches massage therapy in New York City and is the founder of PinPoint Education, abandoned aggressive tissue work a long time ago.

“It’s unnecessarily brutal and irritating. It temporarily masks one pain with another,” she explained. “‘I have a headache so let’s hit my head with a hammer and that will get rid of my headache’ is a backwards way of thinking.” She believes these “brutally distracting” methods aren’t helpful in the long-term.

Photo: Tania Velásquez

At the same time, Velásquez cautions that patient expectations may play a large role in recovery. “I never underestimate the power of distraction + expectation + placebo effect,” she said.

Ultimately, Velásquez believes true tendinopathies are best treated with physical therapy, although massage therapy can provide pain relief, which may make exercise tolerable.

“Plenty of times, however, manual therapy can indeed seem to do the ‘trick.’ But I suspect this is when the condition has been misdiagnosed as a tendinopathy, but is actually a nerve or cutaneous nerve entrapment or irritation,” Velásquez said. “This can be specific or non-specific. Gentle warm ups and/or mobilizations can also function as neural glides, which can help ease these types entrapments.”

Research supports this idea and goes so far as to suggest using the term “-algia” meaning pain, rather than implicating the tendon in these overuse conditions.

Also, myofascial techniques, deep tissue massage and similar massage techniques can all reduce the tensile forces through the tendon. Massage therapists should treat the patient in either a supine position with a slight abduction or side-lying with a pillow or bolster between the knees to avoid allowing the affected hip to fall into adduction.

Foam rolling or the use of other tools that increase compression in the region of the greater trochanter should be avoided.

Gluteal tendinopathy cannot be overlooked when you have lateral hip pain. The relationship between the gluteal tendons and the trochanteric bursa should be front and center when designing and using rehab and management programs for gluteal tendinopathy.

“I’ve never had anyone tell me to go back to doing Cyriax-type frictioning after offering more gentle and effective approaches like DNM. Never ever once,” Velásquez said. “ And yes, I always give them the option to decide which works best for them. There’s sound reasons I’ve stopped using it, and if I ever do use any type of friction anymore, it’s gentle enough to put a baby to sleep and is not for the sake of further damaging tissue fibers under the unnecessary ‘provocation therapy’ claim.”

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.