The terms strain and sprain are often used interchangeably but they are not the same thing. Strains are injuries to muscles and tendons whereas sprains are injuries to joints and ligaments. Neither term would be correct for describing damage to a nerve, however, both sprains and strains can be accompanied by nerve injury.

Strains and sprains are classified by the extent of the injury: mild, moderate, or severe. Typically, these injuries are graded as either grade I, grade II, or grade III based on the amount of tissue damage.

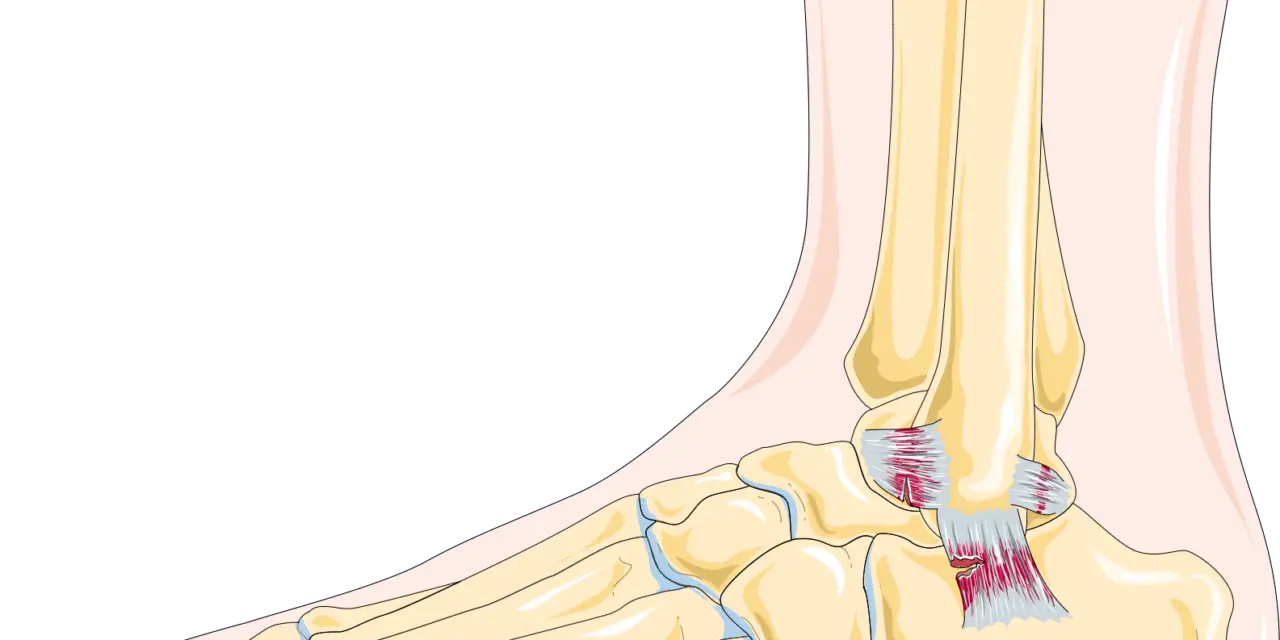

Some common areas for muscle strains include the lower back and hamstrings, but sprains are most common in the ankles, wrists, and knees.

What causes sprains and strains?

Sprains and strains are often caused by accidents, such as a fall, participation in sports, or general physical activity. In short, you’re not likely to get a sprain or strain at rest; you just need to be moving.

Sprains tend to happen with a traumatic event, such as landing on an uneven surface after jumping, a slip-and-fall, or a collision with an opposing player that forces the joint to move outside of the intended pathway.

Strains, however, tend to happen when a muscle or tendon is overstretched or overused. This can happen with direction changes, poor flexibility, or lifting objects that are too heavy for your level of strength.

A good rule of thumb to reduce the risk of such injuries is to avoid doing too much, too soon, and too often. Your body needs time to adapt to the demands being placed upon it (see: SAID principle). Careful attention to the intensity, load, volume, and duration or work can help keep you moving safely and effectively.

Related: [Sprain vs Break: How to Tell the Difference]

Other risk factors for sprains and strains include:

- Sports that involve sudden stops or direction changes

- Skipping your warmup

- Not taking proper rest breaks

- Age

- Level of experience

- Poor flexibility, mobility, or conditioning

- Having a history or previous sprains or strains

- Not maintaining a healthy weight

- Not using the proper equipment, footwear, etc.

- Not completing a full rehabilitation program after injury, surgery, or prolonged illness,

- Performing heavy/demanding work

- Participating in sports or recreational activities without proper instruction or supervision

What are the types of sprains and strains?

The grading of sprains and strains is quite subjective, despite our best efforts to set criteria to help with the process.

In grading strains, to following is generally true:

- Grade I (stretches and mild contusions) describe injuries where only a few muscle fibers are involved, swelling is minimal, and there’s no or minimal loss of strength and range of motion. Grade I strains may only have minimal pain.

- Grade II (moderate stretches and bruises) cause more extensive damage to the muscle and involve loss of function. With grade II strains, you may feel a small defect or divot in the muscle belly and there may be bruising within a couple of days.

- Grade III (severe stretch or contusion) injuries can involve severe pain and a complete loss of function. A gap in the muscle will almost always be felt and the bruising (or ecchymosis) will be extensive.

Grading sprains follows slightly different guidelines:

- Grade I sprains involve a stretching of the ligament without rupture or instability. These injuries are typically slightly tender when touched and do not cause much dysfunction.

- Grade II sprains involve a partial rupture (tear) of the ligament. In these injuries, swelling will be visible and the area will likely be painful. The joint/ligament may or may not feel unstable.

- Grade III sprains are characterized by a complete rupture of the tissues. Pain, swelling, loss of function, and instability will almost always be present.

Related: [Is my ankle broken or sprained?]

What should I do if I get a sprain or strain?

If you suffer a sprain or strain, the first thing you want to do is make sure there’s no obvious deformity. Visual inspection (and pain!) will let you know a joint is dislocated. In these cases, the area should be splinted to the body and you should head to your nearest emergency room, walk-in clinic, or healthcare provider to follow-up.

In less severe injury situations, there are things you can do to promote healing and manage pain. In the immediate management of a sprain or strain, there is still value in using the RICE method.

Your tissues will need time to heal which means you will need to allow the injured area time to rest. Rest can be absolute or relative. While absolute rest looks something like hanging out on the couch catching up on Netflix, relative rest means you continue to do activities—just not the ones that involve the injured area.

An example of relative rest could be someone with a rotator cuff injury taking time off from swimming but continuing to participate in spin classes.

After that, the goal is to control the inflammation so things like ice, compression, and elevation are still helpful.

If things are progressing well after the first 48 hours (decreased pain and swelling, increased function), you can start doing a gentle range of motion exercises, weight bearing, or even light resistance exercises, depending on the injured area. If after 48 hours your signs and symptoms are worsening, consider scheduling a visit with your physician or physical therapist to rule out more severe injury and get you on the road to recovery.

Related: [Can a wrist sprain turn into a fracture?]

Treatments for sprains and strains

Most people are familiar with the acronym RICE when it comes to managing sprains and strains. RICE stands for: rest, ice, compression elevation and has been the main approach to musculoskeletal injuries for decades. Over that time, variations of this plan have emerged as we have learned more about soft tissue healing.

After RICE, there was PRICE (protect, rest, ice, compression, elevation) and then POLICE (protect, optimal loading, ice, compression elevation), and finally PEACE (protect, elevate, avoid anti-inflammatories and ice, compression, education) & LOVE (load, optimism, vascularization, exercise).

At the end of the day, the best approach might just be the one that works best for you.

Exercise

Exercise following a sprain or strain should be graded. Using the services of a physical therapist or athletic trainer can help ensure you are loading properly.

Following an ankle sprain, therapeutic exercises have been shown to reduce the risk of subsequent injury, decrease feelings of instability, improve strength, and decrease time lost from work or sport.

In rotator cuff tendonopathies, exercise is thought to be the most valuable treatment option but clinicians are often uncertain about what exercises are ‘best’ and how to dose them. Several principles have emerged to guide decision making. Programs should focus on exercises that decrease pain, restore range of motion, and improve neuromuscular control. Exercise programs should gradually increase in intensity and complexity.

Exercise is also recommended for people with knee osteoarthritis. In this class of patients, it seems that tasks should focus on improving quadriceps strength, but an overall resistance training program is also quite beneficial. For example, participants in this study improved their leg press power, range of motion, work capacity, balance, stair climbing, and self-reported pain and disability scores while exercising with knee osteoarthritis.

Though it’s not clear how much exercise or what type of exercise is best, It is evident that exercise should be an integral part of your recovery following musculoskeletal injury.

Manual therapy

Manual therapy, an overarching term that includes all types of massage therapy, may also refer to manipulation/mobilization, static stretching, or muscle energy techniques. The journal Chiropractic & Manual Therapies published a scoping systematic review on the effectiveness of manual therapy in the management of musculoskeletal and non-musculoskeletal conditions.

The review included over 170 studies that were primarily systematic reviews and randomized control trials. Notable findings include:

- Manipulation/mobilization may be useful in the treatment of sciatica.

- There is inconclusive evidence for the use of manipulation/mobilization with or without soft tissue treatment in those with neck pain.

- There is inconclusive evidence for the use of manual therapy in conditions of the foot/ankle and elbow.

- There is moderate evidence for the use of manual therapy with exercise in those with rotator cuff pathologies.

- There is moderate evidence for mobilization in the treatment of cervicogenic and miscellaneous headaches.

There is limited high-quality evidence to support the use of manual therapy across body regions.

Related: [Why does the back of my knee hurt?]

Medication

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, either over-the-counter or prescription, are often used following musculoskeletal injuries to help with pain and swelling. Research suggests that these drugs are helpful in the first two weeks of injury management and are associated with complications, such as gastrointestinal upset, ulcers, and perforation.

They are also associated with delayed healing times which has led to many medical professionals to suggest these drugs be avoided.

Other medications/injections, such as venotonic drugs, platelet-rich plasma, topical anti-inflammatories, and hyaluronic acid have also been studied. None of these interventions showed better results than placebo for pain or function.

*This should not be considered medical advice. Please consult with your physician or healthcare professional before starting or stopping any medication.

Electrotherapy

The two main types of electrotherapy (electrical stimulation) used in the management of sprains and strains are transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) and neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES).

Generally speaking, TENS is used primarily for pain control while NMES is used to stimulate muscle contractions. A major benefit of using TENS to decrease pain is that you may be able to start working on a range of motion and strength exercises earlier in the recovery process. For TENS to be effective, it has to be used at a level that is intense but not uncomfortable. Anything less than the strongest intensity that is tolerable is ineffective.

NMES also seems to be an effective intervention for musculoskeletal injuries. It’s believed that NMES generated contractions can assist with edema control, facilitate strength and neuromuscular reeducation, and help decrease pain.

A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis found that patients with knee osteoarthritis reported less pain and more function following the use of NMES. Similar findings were reported by Vaz et al. in their study on the use of NMES to improve quadriceps structure and function in those with knee osteoarthritis.

A 2019 randomized-controlled trial also investigated the use of NMES. In this pilot study, the participants had statistically significant decreases in edema when NMES was used after an ankle sprain.

Should I get a massage for a sprain or strain?

Massage therapy can be useful in the treatment of sprains and strains but it’s not a one-size-fits-all intervention. Mild sprains and strains can benefit from massage to decrease soreness, flush out swelling through improved circulation, decrease anxiety, and reduce muscle tension/guarding.

Moderate to severe strains can likely also benefit from massage, but it may need to be delayed until you can tolerate the touch from a massage therapist’s hands.

There are a few contraindications to massage after injury. If you’re experiencing severe pain or swelling, have open wounds, or a history of blood clots or bleeding disorders, you should discuss your specific situation with a healthcare professional.

The risks associated with massage are generally minimal, but it’s worth noting that you could experience increased pain or swelling, delayed healing, infection, or blood clots after having tissue work done.

If a massage therapist works on someone with a sprain or strain, consider the location of the injury, severity of tissue damage, pain levels, goals of the massage, and the stage of healing before working with them.

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC

Penny Goldberg, DPT, ATC earned her doctorate in Physical Therapy from the University of Saint Augustine and completed a credentialed sports residency at the University of Florida. She is a Board Certified Clinical Specialist in Sports Physical Therapy.

Penny holds a B.S. in Kinesiology and a M.A. in Physical Education from San Diego State University. She has served as an Athletic Trainer at USD, CSUN, and Butler University.

She has presented on Kinesiophobia and differential diagnosis in complicated cases. Penny has published on returning to sports after ACL reconstruction and fear of movement and re-injury.

Outside of the clinic, Penny enjoys traveling, good cooking with great wine, concerts, working out and playing with her dogs.