Case studies are often considered as low-quality evidence in the scientific hierarchy of evidence, but sometimes they can shed some insight, evoke new questions, and help us understand an unfamiliar topic better with storytelling. Because case studies are often narrated like a story, the information tends to get retained better than plain data. The case of Russian composer and pianist Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) and his chronic pain in his right hand is one great example of how the biopsychosocial model of explaining pain applies in understanding pain.

Scriabin grew up in a nurturing aristocratic family in Moscow. His mother was a gifted pianist, who died when he was one, and his father was a diplomat. As a teen and young man, Scriabin was as ambitious as many American Idol contestants in being famous and being one of the best among his peers.

He studied as the Moscow Conservatory between 1887 to 1892 where he graduated with a diploma in piano. (1) His reputation and musical talent spread during his travels throughout Europe and the United States during a six-year tour between 1903 to 1909. However, after his death and the Russian Revolution, Scriabin’s musical influence and significance in the Soviet musical scene declined. His work later was re-evaluated and lauded as comparable to Beethoven’s works decades afterward. (2)

Since age 20, Scriabin suffered from a chronic right hand pain that no physician at the time could identify specifically the cause or treat. The general diagnosis was “paresis,’ which was a broad term to identify a general weakness or a partial loss of voluntary movement. Back then, physicians did not distinguish paresis from having pain or no pain.

Dr. Grigory Zakharin, who was a nerve disorder specialist who treated Scriabin, attributed his pain from a horse carriage accident that Scriabin was involved in at age 14, fracturing his right collarbone. He told him that his paresis was incurable, and ordered the ambitious pianist “to abstain from all practicing and prognosticated the end of his career as a public performer.” (2) After that, Scriabin began to practice playing on the piano with only his left hand, which later affected his future compositions.

Doctor Shopping and Interesting Treatments

Scriabin consulted another physician, Dr. Alexander Belyaev, chief physician at the Surgical Clinic of Moscow University, who suggested that the pianist should adopt a “regular and tranquil life, bathing in seawater, and consuming a diet of kumiss.” (2) Kumiss is a traditional Tartar and Mongol dairy product that was touted as a cure-all back then.

On May 1895, Scriabin consulted another nerve specialist in Germany, Dr. Wilhelm Erb, who was a professor of nervous disorders at Heidelberg University. His prescription was “hydrotherapy in Switzerland—a four week course of this at Schöneck on Lake Vierwaldstettersee—then a journey through Switzerland and finally sea bathing in Italy,” Scriabin reported. (2) Despite Dr. Erb’s extensive knowledge of the nervous system, his prescription was no more effective than taking kumiss.

The pain did not stop Scriabin from continuing to perform and compose. In fact, his paresis may given his compositions a different flavor than other contemporaries. While his physicians could not give him adequate treatment or care nor was his case , modern understanding of pain and neuroscience provide some clues and hypothesis to why this talented musician had chronic pain.

Examining the Evidence

Neurologist, neuroscientist, and musician Eckart Altenmüller from the Institute of Music Physiology and Musicians’ Medicine at the University of Music Drama and Media in Germany examined some of the treatments and diagnosis that Scriabin’s physicians had made.

He stated that Dr. Zakharin’s diagnosis where Scriabin’s accident have contributed to his paresis at age 14 is correct. “Theoretically, an irritation of the brachial plexus would have been possible shortly after the bone fracture—for example, due to callus tissue accompanying bone healing.” (2) There were also no reports or evidence that the pain from the injury occurred during past six years before Dr. Zakharin’s diagnosis. Scriabin was able to practice and play without pain during that time.

Even if there were some sort of nerve damage or pathology in the brachial plexus, Dr. Erb would not most likely to have missed it. “A compression of the upper fascicle of the brachial plexus, below its passage under the clavicle, would have caused tingling, paresthesia, and muscular atrophy, symptoms which would have never been missed by Professor Erb, who was famous as a specialist for the brachial plexus.” (2)

There was also no evidence that Scriabin had rheumatism because there were no reports of swelling, inflammation, pain in the morning or at night, or rheumatic nodules. Some experts say that Scriabin may have had musician’s dystonia, which is a movement disorder with a loss of voluntary control due to extensive musical practice.

However, pain isn’t usually a symptom of musician’s dystonia, and if Scriabin had that, he would not have been able to write legibly. His notes and composition would resemble spidery scribbles.

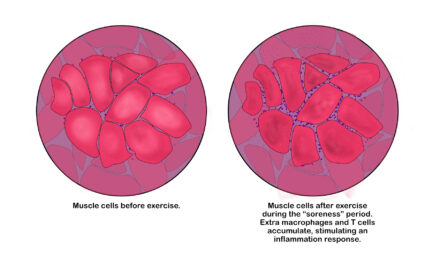

Altenmüller identified two symptoms that Scriabin exhibited that may be indicative of myofascial pain syndrome: Dull shifting pain caused by excessive strain on muscles, joints, and other soft connective tissues that get worse with exertion and lack of motor agility with increased muscle tension. Thus, most pianists often get pain in their fingers, wrists, hands, shoulders, and neck. It only occurs when the musicians play their instrument, not while doing other physical activities.

While Alexander Scriabin’s quest for a cure for his right hand pain have yielded little benefits, today’s aspiring musicians and healthcare professionals who work with many musicians could learn much from the young Russian artist’s case — from his strive to become the greatest pianist at his time to the course and treatments of the pain that he had experienced. Understanding the underlying principles of pain could help us get a step closer to find better solutions and communication to our clients and patients.

Yet despite Scriabin’s near life-long suffering of pain and delusions, his work is considered as one of the greatest masterpieces that few pianists could emulate. A constant pain could change the homuncular topography, which can distort or exaggerate the normal sensation in a body part — in Scriabin’s case, his right hand. (3) This change correlates to pain memory and can flare up during music practice.

Altenmüller stated that “a crucial part of therapy is to allay the patients’ anxieties in order to break the vicious circle of feeling under threat and prevent the pain from becoming fixed in the pain memory.” He also suggested that musicians with chronic pain should practice no more than ten minutes at a time with several practices a day.

In fact, this is likely why Scriabin’s piano teacher, Vassily Safonoff, had the young student practice less technical and demanding compositions, such as Mozart’s work. He didn’t tell him to stop practicing or force him to do more than necessary.

However, Dr. Zakharin gave young ambitious Scriabin a “death sentence” by telling him that he will never achieve his “high-flying goals, which only increased the pianist’s psychological stress and decrease his pain threshold. (2) Other psychological and sociological factors that likely contributed to his pain would include his financial issues, martial problems, and ability to work under pressure. Scriabin’s fear of failure and “type A” personality may also be major psychological contributing factors. (1)

References

1. Starcevic V. The life and music of Alexander Scriabin: megalomania revisited. Australasian Psychiatry. 2012 Feb;20(1):57-60. doi: 10.1177/1039856211432480. Epub 2012 Jan 9.

2. Altenmüller E. Alexander Scriabin: his chronic right-hand pain and Its impact on his piano compositions. Progress in Brain Research. 2015;216:197-215. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2014.11.031. Epub 2015 Jan 29.

3. Henry D., Chiodo A., Yang W. Central nervous system reorganization in a variety of chronic pain states: a review. PM&R 2011 Dec;3(12):1116-25. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.05.018.

A native of San Diego for nearly 40 years, Nick Ng is an editor of Massage & Fitness Magazine, an online publication for manual therapists and the public who want to explore the science behind touch, pain, and exercise, and how to apply that in their hands-on practice or daily lives.

An alumni from San Diego State University with a B.A. in Graphic Communications, Nick also completed his massage therapy training at International Professional School of Bodywork in San Diego in 2014.

When he is not writing or reading, you would likely find him weightlifting at the gym, salsa dancing, or exploring new areas to walk and eat around Southern California.