Clinicians are likely to trust peer-reviewed studies, but the peer-review process is often a mysterious one and riddled with errors.

Why do we have peer review? What does it do well and where it sometimes falls short? What are the current challenges in the peer-review system, and what actions the research community is taking to address them?

For massage therapists and other manual therapists who are interested in the behind-the-scenes process in research publication, this is a basic necessity to help evaluate the validity of a study.

This is also crucial in our current information-rich society and has been described as “the ability to identify what information is needed, understand how the information is organized, identify the best sources of information for a given need, locate those sources, evaluate the sources critically, and share that information. It is the knowledge of commonly research techniques.” (1)

Therefore, information literacy requires the ability to distinguish among popular media (newspapers and magazines, visual media, internet sites, blogs, editorials, etc.), trade media (trade publications, marketing materials, advertisements, etc.) and academic media (research journals, university-press books, textbooks, etc.). (2) Although editors and fact-checkers assess copy accuracy and writing quality to a certain extent, popular and trade media are not peer reviewed. This information is meant to entertain, persuade, and grab attention to gain a wide audience and is not primarily intended to be purely education or factual. In contrast, academic media, such as research and clinical journals, are meant to factually inform a niche audience of specialists and professionals, and the content is carefully reviewed by a subset of those specialists prior to publication. (3) Why do we trust peer-reviewed studies?

Peer reviewed information can be assessed, replicated, and sorted into the larger picture of the best knowledge gained (thus far) and is curated by the research community via a self-policing process. (4)

Setting aside the deluge of popular and trade media that offer claims, advice, and opinions on health, fitness, and medical topics, this article focuses on the peer-reviewed literature, specifically on publication of research and study findings in academic journals and the process that occur behind the scenes.

Nuts and Bolts of Peer Review

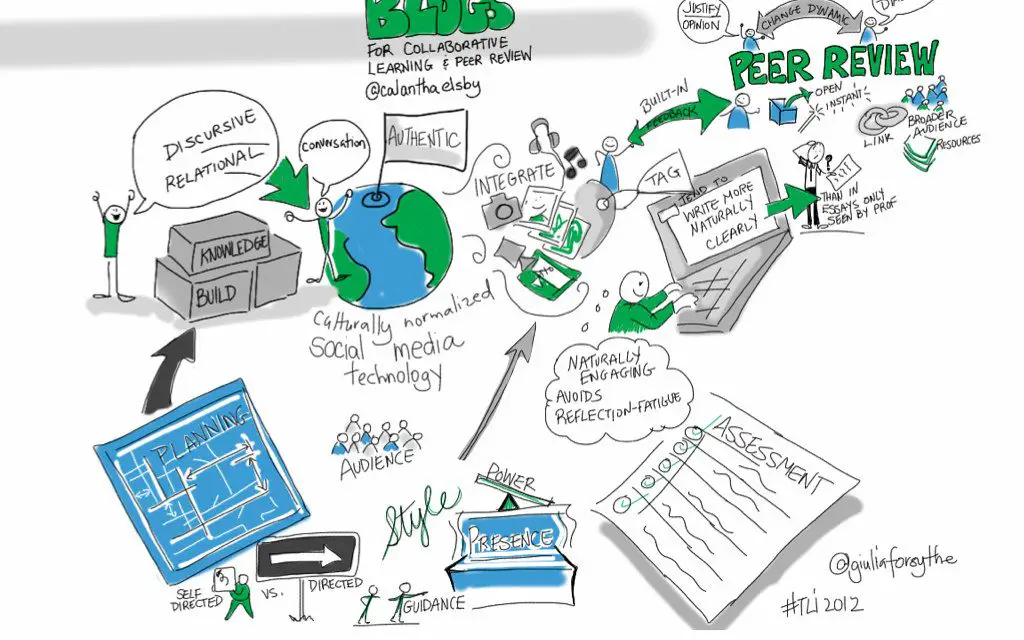

Peer review is the umbrella system that reviews and assesses the quality and originality of research findings prior to formal publication. It is designed to sift out unfinished, unclear, unoriginal, or insignificant findings and to make immediately available the most important and relevant results to the entire research community. Peer review is often associated with the pre-publication review process in which research findings are assessed and revised by a journal editor and a few experts in the field, known as reviewers or referees.

However, this phase is only one aspect of the larger peer review process. Full peer review consists of research peer review (prior to journal submission), pre-publication peer review (by the editorial staff and reviewers), and post-publication peer review (by fellow researchers who attempt to replicate or build on newly published findings).

Despite all the editing and review it goes through, pre-publication peer review is neither a guarantee of accuracy nor a fraud detection mechanism. When a study is retracted or fraudulent research results are uncovered, what we are witnessing is the peer review system in action. If a flawed study gets through the first two stages of peer review, it is usually found out (and rather quickly) in the post-publication peer review process, because peer review encompasses much more than the pre-publication step.

Alternatively, peer review is not gate-keeping mechanism intended to shut out maverick investigators or outsiders; it focuses only on quality of information. According to the scientific method and professional principles, a good idea is a good idea no matter who discovers it if it can be supported by evidence after rigorous review. In reality, many claims fall apart when subjected to critical scrutiny of the strength of evidence and the controls required to rule out alternative hypotheses or confounding variables.

For this reason, so-called ‘breakthroughs’, astounding findings that are announced first in the popular media or on the internet, should be immediately viewed with skepticism because they have not been subjected to peer review.

Phases of Peer-Review Process

1. Pre-publication

The first phase of peer review is conducted continuously throughout the process of research, beginning with informal discussions of experimental designs and preliminary results among the lab group. The experimental design, controls, measurements, methods, and statistical treatments are endlessly questioned, analyzed, improved, and refined throughout this process. Preliminary results are prodded for weakness, alternative interpretations, sources of error, biases, and whether the results fit with or challenge other accepted evidence.

More formal discussions take place when those findings are shared with other research personnel in presentations at departmental seminars, review with collaborators and granting agencies, and presentation at scientific meetings and conference sessions.

An important component of training for researchers is learning how to work within the culture of continuous informal peer review and challenge, during which early-career investigators learns to objectively assess their own work and that of others, to separate discussion of the data from one’s personal investment, to question assumptions and look for alternative explanations, and to solidly support conclusions with convincing evidence.

2. Pre-publication peer review

Once the manuscript is submitted, the journal’s editorial staff either rejects it outright or passes it on to the second phase of peer review. Qualified reviewers (usually three research professionals who are experts in the subject area) are assigned to review the manuscript and are given a timeline within which to submit a detailed critique with questions for clarification, suggestions, etc. and a recommendation for or against publication. The results of this review are sent back to the authors for formal response. This process is repeated as necessary until the manuscript is deemed ready for publication.

3. Post-publication peer review

After publication, the study is read, discussed, and critiqued by the scientific community at large. Individual scientists or research groups might directly correspond with the study authors, and scientists working in related areas of inquiry discuss and utilize the results in their own work. The experiments, methods, and findings in the published paper are tested via repetition and validated as other scientists attempt to build on these findings. The study is cited as supporting evidence in subsequent publications, and the work becomes a minor or major piece of the larger body of knowledge.

If the work contains major flaws or cannot be replicated, the journal and the scientific community are alerted and informal/formal investigations follow. The research team might issue a correction or withdraw the paper, or the journal can retract the paper. Fraud or misrepresentation is handled through individual institutions and/or governmental and other funding agencies. Rather than signifying a failure or a broken system, these corrective instances demonstrate the rigor of the full peer review process. Two recent instances of retracted studies are discussed later in additional detail.

Reviewer selection and evaluation process

Peer review highly depends on the availability, expertise, and willingness of researchers to participate in the process. Each journal’s editorial staff maintains a database of qualified reviewers. However, to ensure that the reviewer database is up to date and to spread the workload among reviewers (who donate their time and expertise), authors are often asked during the submission process to suggest names/emails of their peers who might be good reviewers for the manuscript.

Typically, these suggested reviewers are researchers who work/publish in the same scientific/clinical niche and are up to date on the literature, the direction of the latest research, and the open questions/unsolved controversies in the field. In other words, the reviewers are fellow researchers who have the necessary background to be able to thoroughly assess the details of the paper.

Authors can also request that a particular person(s) is NOT assigned as a reviewer; this practice is intended to reduce personal biases and/or avoid professional conflicts, perhaps with competitors or particularly contentious persons in the field (who might have incentive to provide critical review to slow the publication process and give themselves additional time to “scoop” the author). If authors are unaware of the names of the reviewers, the process is one-way blinded; if the names of the reviewers and authors are unknown to each other, the review process is double-blinded.

There are advantages and disadvantages to both systems, but in small fields of study in which the active researchers are well known, it is often fairly easy to figure out who is participating on either side of the review, regardless of the blinding process.

When Reviews Go Rogue

Cracks in the peer review process have appeared in several forms, and several of these instances have been covered in the popular media. However, these issues have surfaced due to a variety of underlying causes. Outright research publishing can and does occur due to publication in predatory or “pay-to-publish” journals that have cropped up with the advent of low-cost online publishing and increasing pressure on researchers to continuously publish.

These journals do not have a formal peer review process or maintain the appearance of a “rubber stamp” peer review process that does not assess the quality of the research, and authors simply pay a large fee to publish their manuscript.

To prove the existence and extent of this market, researchers conducted an experiment in which they generated poor quality manuscripts with glaring flaws and submitted them to a variety of allegedly legitimate journals. The journals with a bona fide peer review process tended to identify the bogus manuscripts and reject them, but the low-quality predatory journals were willing to publish them for a hefty fee. (5)

Without a deep knowledge of the reputations of individual journals within a certain subfield, it is increasingly difficult to assess the quality individual journals. In response, Beall’s list of suspected predatory publishers and journals is maintained by an academic librarian at the University of Colorado-Denver in the U.S. (6,7)

Generally, the more prestigious the journal, the more rigorous and selective the peer review and reviewer screening process will be. However, even the elite journals (e.g., Science, Nature, Cell, etc,) have been criticized for their high rates of retraction, not always due to outright fraud, but often the result of hasty publication of material that was not complete or completely verified (e.g., mistakes in the manuscript or experimental methodology, replication problems, oversights on controls, etc), the equivalent of a posh restaurant serving an omelet that is still runny in the middle.

In the race to publish the latest “hot” findings, certain of the checks and balances (and patience for the slow and thorough review process) are becoming strained, as noted in several editorials by science professionals that have appeared in the popular press.(8)

Fraudulent Reviewers

Two recent examples of retracted studies and fraud issues within the peer review process have appeared in the general news media. In April 2015, the British publisher BioMed Central (BMC) was forced to retract over 40 published research studies because the peer reviewers of these papers were found to be associated with a ring of fraudulent or nonexistent reviewers as part of an engineered effort to push submissions through the publication process, possibly enacted by a third party. The authors of the retracted papers, who may or may not have been aware of the fraudulent reviews/reviewers, were all based in China, where political and economic pressures on science productivity are high. (9)

An increasing number of manuscript submissions have resulted in a scarcity of reviewers, and BMC, like many journals, relied on author suggestions to meet the demand.

Inevitably, this situation led to one in which a small group of individuals saw an opportunity to game the system. Since the scandal, BMC has temporarily suspended their reviewer suggestion process and is redesigning their submission process and review process.

Many journal editorial boards ask for reviewer suggestions because of the short supply of reviewers. Peer review is an unpaid professional service that researchers contribute to science and to their community. Also, payment for review brings up possible ethical and conflict of interest issues. However, as the current research funding crunch and productivity pressures mount, researchers find themselves running low on resources and are required to spending more time submitting grant proposals and working to publish findings that will secure new grants and publications and show progress on current grant deliverables. (8, 10)

Unpaid service tends to drop down the priority list, and currently, researchers do not review as many submissions as in the past. It takes a considerable amount of time and effort to complete a thorough review, and if the existence of one’s lab group is on the line, researchers turn to the most important and most rewarded task at hand, which is producing their own research. (11,12)

Additionally, the suggested reviewers are not likely assigned to review the suggesting author’s manuscript. The editorial staff might use one of the suggestions in addition to their “usual” reviewers for balance and/or the reviewer suggestion process might be intended keep up with the growing number of publication submissions. In North America, depending on the relative prestige of the journal (and the authors and the reviewers), verification of the names and credentials of the reviewers is fairly straightforward, but this task becomes more complicated with distance and across borders as research becomes a global activity.

Fraudulent Data and Findings

Another more recent story made the popular press because it has ties to current political/social issues in the United States. (13) In December 2014, a study originally published in Science, one of the flagship research journals, claimed that social science researchers were able to successfully change potential voter opinions on the issue of same-sex marriage using a strategy that sent gay and lesbian canvassers to voters’ homes for a personal conversation. (14) By early 2015, another group of researchers reported that they had encountered difficulties in replicating the study results, and an investigation was launched. It appears that one of the co-authors may have allegedly falsified data, was not able produce the raw data used to support the original study, and also may have falsified his funding sources. (15)

On May 2015, the other co-author of the study formally requested that Science retract the paper, and formal investigations are pending. This event raised the profile of the existing question of whether/how raw data should be made available for verification and replication purposes.

In many cases (including this one), concerns over access to personal information and privacy requirements cloud the issue, especially if clinical/medical information or demographic data are involved.

Another more practical issue is the sheer logistics of where to submit, store, catalogue, and maintain sets of raw data and requirements for determining secure access to the data. These issues are currently under review by several working groups within the research community who have put out recommendations for improving the peer review process. (4,12,16)

Strengths, Improvements, & Structural Challenges

The good news is that in both of these cases, the post-publication peer review process uncovered the fraud, exposed weaknesses in the current system, and underscored potential issues in the larger structural architecture of research support and reward. There are several major observations that should be noted from these events. First, these events should not be viewed as evidence that all science is suspect or corrupt or that we should throw out peer review, but in light of the rapid global expansion in research activity and the availability of internet publishing, the scientific research review and publishing process must be revamped and improved with additional checkpoints and requirements for supporting data.

Sense About Science is an example of how the scientific community is addressing these issues. As part of its mission to address the use of scientific and medical claims in public discussions, this multidisciplinary trust has published a series of guidelines intended for lay people concerned about the quality of science information (3) and early career researchers (17) as well as a formal assessment and recommendations for the peer review process. (4) Scientists and researchers have also directly addressed the public in several articles and editorials that have appeared in the popular press and internet media.

Image: James Eade

The peer review process is also used to rank and recommend research proposals for grant funding, and a recent study that assessed the quality of granting peer review concluded that the process was robust and in good health. High scores from peer review of grant proposals were correlated with higher frequency of publication, higher numbers of citations, and publication in higher-impact journals. (18)

A second important observation is that the incentives and pressures in the current research system are not in line with the preferred outcomes of the scientific research process. (8,16) In short, the current atmosphere for research and the demands on researchers are resulting in unintended consequences (including fraud and other shortcuts to good research) from ill-designed incentives. (10) Governments and other funding agencies have continually cut research funding at the same time that demands for research productivity have increased. (19,20)

A larger number of researchers are competing for a dwindling pool of grant funding and positions in research institutions and “publish or perish” has never been more of an imperative. (8,10) The corrosive results of short-term incentives and emphasis on financial competition on other institutions and businesses around the world offer a cautionary tale that forces the question of how we value research and quality of knowledge in the global community.

Finally, given the observation that mistakes and fraud can occur in information that has been subjected to the peer review process, we should look even more skeptically at information that has not been submitted to any review process. The state of scientific knowledge rests on the body of evidence and not on any single study. The process of peer review is cautious and takes time to sort out the relevant and valid information that will contribute to defining the overall state of the best that we know so far.

The leading edge of knowledge is always fuzzy and not yet clear, which is even more reason to take cautious approach to new information and examine new findings in the context of other accepted information.

Dr. Molly Gregas can be reached at gregasmk@gmail.com.

References

1. “Information Literacy – Home.” Information Literacy – Home. Accessed May 28, 2015. http://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/info_literacy/

2. “What’s the Difference between Science and Pseudo-science?” Violent Metaphors. May 17, 2013. Accessed May 28, 2015. http://violentmetaphors.com/2013/05/17/whats-the-difference-between-science-and-pseudo-science/

3. I Don’t Know What To Believe: Making Sense of Science Stories. Sense About Science.

4. Peer Review and the Acceptance of New Scientific Ideas: Discussion Paper from a Working Party on Equipping the Public with an Understand of Peer Review. Sense About Science.

5. Bohannon, John. Who’s Afraid of Peer Review. Science 342, no. 6154 (2013): 60-65. doi:10.1126/science.342.6154.60.

6. LIST OF PUBLISHERS. Scholarly Open Access. January 15, 2012.

7. LIST OF STANDALONE JOURNALS. Scholarly Open Access. January 17, 2012.

8. Marcus, Adam, and Ivan Oransky. “What’s Behind Big Science Frauds?” The New York Times, May 22, 2015, The Opinion Pages sec. Accessed May 28, 2015.

9. Major Journal Publisher Admits to Publishing Fabricated Peer Reviews. ScienceAlert. March 30, 2015. Accessed May 28, 2015.

10. Scalas, Enrico. Do Pressures to Publish Increase Scientists’ Bias? An Empirical Support from US States Data. PLoS ONE 5, no. 4 (2104). Accessed May 28, 2105. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010271.

11. Harris, Richard. When Scientists Give Up. NPR. September 9, 2014. Accessed May 28, 2015.

12. Daniels, Ronald J. A Generation at Risk: Young Investigators and the Future of the Biomedical Workforce. PNAS. 112, no. 2 (2015): 313-18. Accessed May 28, 2015. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418761112.

13. Carey, Benedict, and Pam Belluck. “Doubts About Study of Gay Canvassers Rattle the Field.” The New York Times, May 25, 2015, Science sec.

14. Glass, Ira. “Canvassers Study in Episode #555 Has Been Retracted.” This American Life. May 20, 2105. Accessed May 28, 2015.

15. Kolowich, Steve. “‘We Need to Take a Look at the Data’: How 2 Persistent Grad Students Upended a Blockbuster Study.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, May 21, 2015, Research sec.

16. Drezner, Daniel W. “Fact, Fiction, and Social Science Replication.” The Washington Post, May 28, 2015, Post-Everything sec.

17. Peer Review: The Nuts and Bolts for Early Career Researchers. Sense About Science.

18. Does Peer Review Ferret out the Best Science? New Study Tries to Answer. Retraction Watch. April 23, 2015.

19. Rockey, Sally. Comparing Success Rates, Award Rates, and Funding Rates. NIH Extramural Nexus.

20. Howard, Daniel J., and Frank N. Laird. The New Normal in Funding University Science. Issues in Science and Technology. 30, no. 1. Fall 2013.